Body

State lotteries, which traditionally raise money for college scholarships or senior citizen services, are facing a range of threats and opportunities as more forms of legal and illegal gambling have become available to the U.S. consumer.

Opportunities for growth range from collaborating with courier services to legalizing iLottery in more states, while unregulated or grey-market gaming machines, also known as skill-based games, continue to threaten the long-term viability of the industry.

Not since 2020 when Washington, D.C. legalized its internet lottery has iLottery moved forward in the U.S., said Jim Schultz, executive vice president for global public policy and government affairs with Scientific Games.

“It’s been very stagnant,” Schultz said.

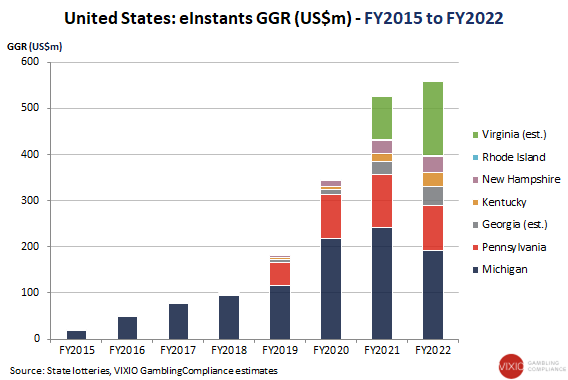

Currently, there are ten state lotteries offering iLottery. They are Illinois, North Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

“I think it’s because states have money, but that is not going to continue,” Schultz said. “There was this huge infusion of money from the federal government [in COVID-19 stimulus funds]. If we wait until states begin to run out of money to get iLottery across the finish line, we are going to be behind.”

Schultz said that as far as state lotteries are concerned, iLottery is about modernization and being competitive, more than just a driver of revenue.

“It’s about everyone using their phones for various forms of gaming, but it is also about making sure the lottery is sustainable,” he added. “If we don’t act soon in a lot of states, legislators are going to be forced to make some tough decisions regarding tax increases … to support the programs the lottery supports.”

Schultz told attendees on Friday (July 14) at the National Council of Legislators from Gaming States (NCLGS) summer meeting in Denver that the industry has made some progress lobbying legislators in New York and other states to consider introducing iLottery bills.

He attributed that progress to “shoe leather lobbying, and people have seen the value” of iLottery.

“It is easy to say retailers will suffer,” Schultz said during a panel discussion on lotteries. “[Pennsylvania] is Exhibit A why the retailers don’t suffer. There are incentive programs in Pennsylvania. We’ve seen an increase in scratch-off sales.”

“All of us have to work together and create a campaign and push it forward,” he said.

In Pennsylvania, the state lottery reported $5.5bn in retail sales, $900m in online sales and a profit of more than $1bn last year.

But Drew Svitko, executive director of the Pennsylvania Lottery, said the lottery operates in a crowded gaming market.

“We are second to Nevada in the number of slot machines,” Svitko said. “But that’s okay. We do have an iLottery program, which we launched in May 2018. It helps us stay relevant in a crowded market.”

Bishop Woosley, former director of the Arkansas Lottery and now a senior advisory with Jackpocket, admitted that he was always jealous of Svitko being in a state that was a lot more progressive when it came to gaming.

“Arkansas not so much,” Woosley said. “I come from the other side of the street where we couldn’t have been as nimble.”

He described himself as an advocate for the courier service Jackpocket because in Arkansas the courier filled a niche that could not be served by a state-operated iLottery program. Courier services operate by allowing players to create online accounts and order state lottery tickets through their phones.

Tickets are acquired by the couriers from licensed retailers, with players either receiving winnings directly into their accounts or a notification when they win a larger prize.

In terms of threats, Woosley expressed concern that some state legislatures were cutting advertising budgets, making it more difficult for lotteries “to speak with their players, advertise to their players and compete with iGaming, sports betting and casinos” and their sophisticated marketing campaigns.

Svitko told some 300 attendees that he is also concerned about competition from other forms of entertainment, noting that lotteries sell “a product that people don’t need.”

“It’s an impulse item for most people and that means [there is competition from] anything else someone can spend their discretionary dollar on,” he said. “That could be other forms of gaming or any other form of entertainment. So, a threat for the lottery, is thinking there isn’t competition out there.”

Svitko said the most serious threat to the Pennsylvania Lottery comes from unregulated gaming.

Various states including Virginia, Pennsylvania and Missouri have struggled to contain the growth of grey-market machines.

“There is no regulation on these machines,” said Lester Elder, director of the Missouri Lottery. “The estimates are 15,000 machines. I would say that’s probably low. They are just everywhere.”

Elder said grey-market machines have been around for many years in Missouri but since 2018 or 2019 they have “just vaulted everywhere.”

Not only are these machines not regulated, but Elder was also concerned that without exclusion lists these so-called skill-based games are attracting problem gamblers.

“I’ve walked in to stores and saw people that you know shouldn’t be playing and are probably problem gamblers. These machines are a problem.”

Schultz of Scientific Games estimated a total of 580,000 grey machines in the country.

“It is a huge percentage of gaming in this country and these folks are unregulated,” he added.

.svg)